Lasting Images: The no photo policy

When Ankali introduced cell phone camera stickers, which every visitor must get placed on their lenses while being checked upon arrival, I noticed some raised eyebrows and nervous mumbling on the faces of regular visitors and newcomers as well. As a result, it takes a bit longer to get in, and a lot of people might think it’s an over-reaction from the club’s side. It also appears to be a simple mimicking of the methods other foreign clubs use.

During my photography studies I have become aware of the problematic aspects of this omni-present medium. For my final master thesis I delved into the relationship between clubbing and photography – into the clubs’ photography policies and bans specifically. When it comes to the stickers, they are a mere extension of a club’s no photo policy: a present physical obstacle; a symbolic gesture of the policy; a moment to think twice when seeing something which seems necessary to capture. What I think it’s maybe worth of further explanation, is the no photo policy itself.

Few snaps of history

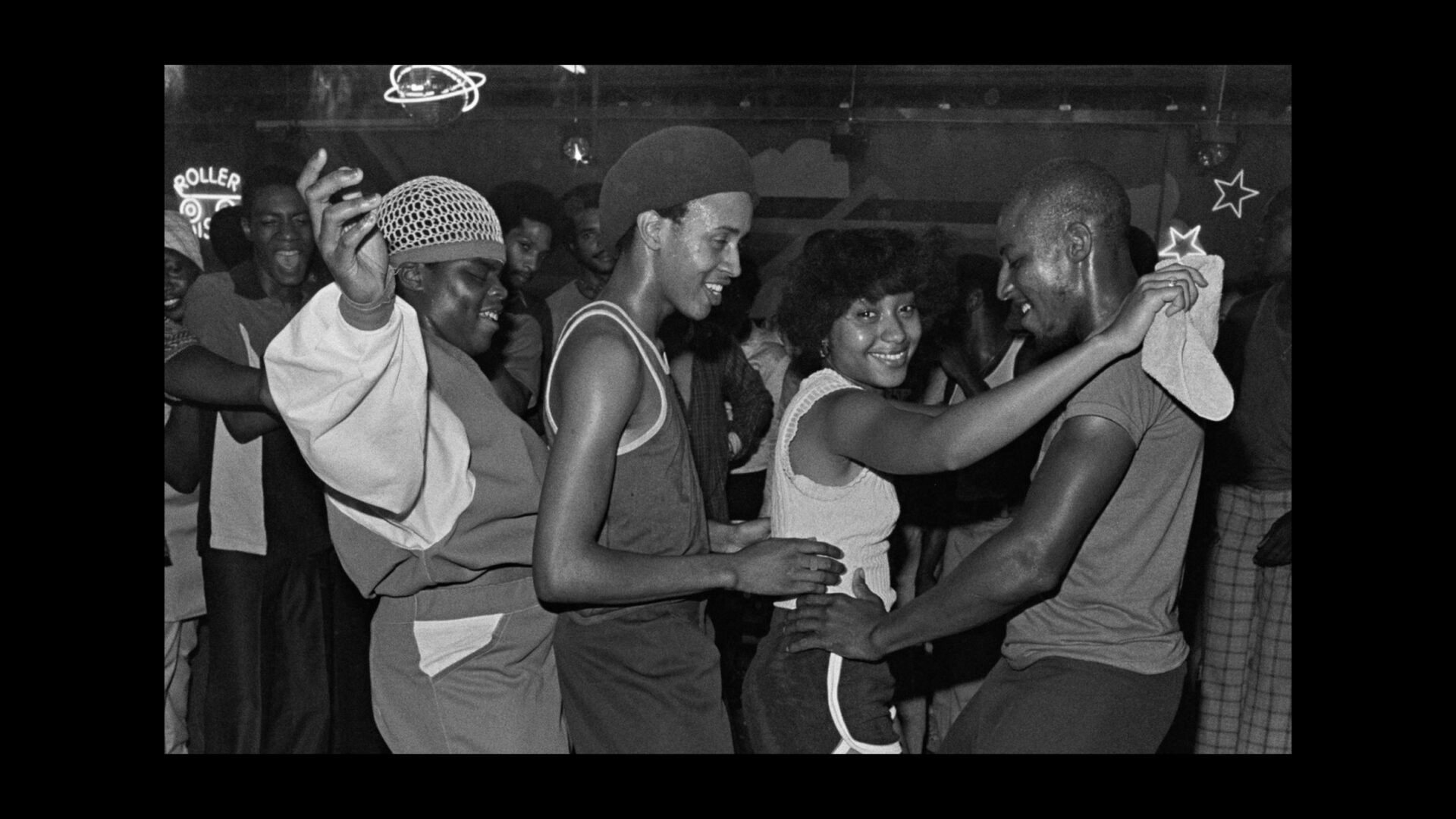

The obsession for visual accounts of the things happening inside clubs was already apparent in the late 70s. As disco music spread further along with multiplying venues, some people with cameras and with an interest started taking pictures. Meryl Meisler, Waring Abbott, Gene Spatz and many others focused on celebrities visiting clubs like Studio 54, Xenon or Hurrah. If you have ever seen photos of Andy Warhol or Grace Jones with shiny outfits and eagerly posing companions, these guys are possibly the authors. Spatz was even considered to be one of the pioneers of paparazzi.

The owners of Studio 54, Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, cracked the formula for being in the centre of attention by introducing an authoritative door policy, while allowing hedonistic democracy inside their infamous club. They have managed to get all the celebrities in, created a very indulgent atmosphere, thus encouraging a demand for certain kind of images in the midst of growing celebrity culture, while becoming rich personas in demand as well. Although a majority of these images became widely available much later, there weren’t that many channels for them to travel through at the time when they were made.

Studio 54 (1977) by Bill Bernstein

Studio 54 got shut down after 3 years for tax fraud and celebrities started avoiding the nightlife spotlight. Later a new group of people filled a hole left by show business stars: Club Kids. Mostly looking for escapist adventures in clubs like Limelight or Palladium, Club Kids were a trend-setting bunch of young people, who embraced clubbing as their lifestyle. Media covered their hedonistic behaviour, their provoking or absurd fashion choices and crazy themed parties (e.g. Blood Feast). A lot of people wanted to be a part of it, some were following them from the outside, some of them even considered moving to NYC to join. Club Kids became a phenomenon which represented the underground and exclusive nightlife and they became a lens through which the public perceived the club culture.

Astro Erle at Limelight (1992) by SKID

Digital outbreak

In her thesis about the impact of digital photography on NYC club scene the author Lisa Helen Richman describes the radical shift in the popularity of club culture propelled by the arrival of the internet. She emphasizes that nowadays club culture differs from the past due to the unlimited access to the images from culture’s insides that the world wide web has allowed. Images of the previous club eras were very limited to analogue photographic processes and the culture’s higher exclusivity. Digital photography spread via the internet had increased the speed and depth into which mass culture appropriates once exclusive realms. As the scenes kept popping around the world and growing, so called party photographers kept taking pictures uniformly and feeding various famous online platforms, benefiting social statutes of clubgoers and big commercial brands which advertise their products in between.

Club culture became over-exposed, turning from a subculture into a mass one. A photograph from a party became a commodity or a point in social score-keeping. I am sure you remember geeky early-web portals with galleries of 150+ photos from each and every party happening someplace. If you don’t, visit the photo section of any random tourist super club profile on facebook, this thing is still alive.

The absence of camera

In my research I have examined photo policies of four clubs to help me understand possible reasons for regulation: Ankali, De School (NL), Berghain (DE) and Smartbar (US). I have taken into account information available publicly, sent questionnaires, but also drew from my own personal observations from these places (apart from Smartbar). There is always a more complex reasoning behind each policy, not just one specific purpose.

The most obvious problem is the presence of the camera or a physical act of taking a picture. Good clubs are usually intimate and dark places, where the space is designed to accentuate the music and light orchestration. It is certainly annoying to have a quantum of smartphone screens in around you and flashes bursting frantically. Michal Veltruský, one of the founders of Ankali, believes that a club night is about balancing the symbiosis of the sound, lights and people’s behaviour on the dancefloor. The emphasis on sustaining the collective energy of the crowd, which is experiencing that ‘here and now’ together, is what usually comes up as the most important factor of Ankali’s no photo policy in conversations with Michal. Too much attention paid to the screen of the phone, or to the outside world and its immediate feedback, disrupts this special shared experience.

The presence of the camera can also increase the self-awareness of some visitors, who would much rather not care, dive into the atmosphere and get lost in themselves. That’s what Martin Savenije, former photographer associated with the Trouw club (De School’s predecessor) wrote, when he took the task of explaining the photography ban in the venue’s final year. ‘A preoccupation with the image I’d like to present to the world hinders the blissful music-induced state of dissociated consciousness.’ Furthermore, the need to take a picture can lead to intolerant and rude acts – elbowing one’s way to the front, not respecting dancers’ personal space. Or as seen at this Boiler Room event in Budapest, it can also make douchebags be extremely intrusive towards the DJ during his performance.

The emphasis on sustaining the collective energy of the crowd, which is experiencing that ‘here and now’ together, is what usually comes up as the most important factor of Ankali’s no photo policy…

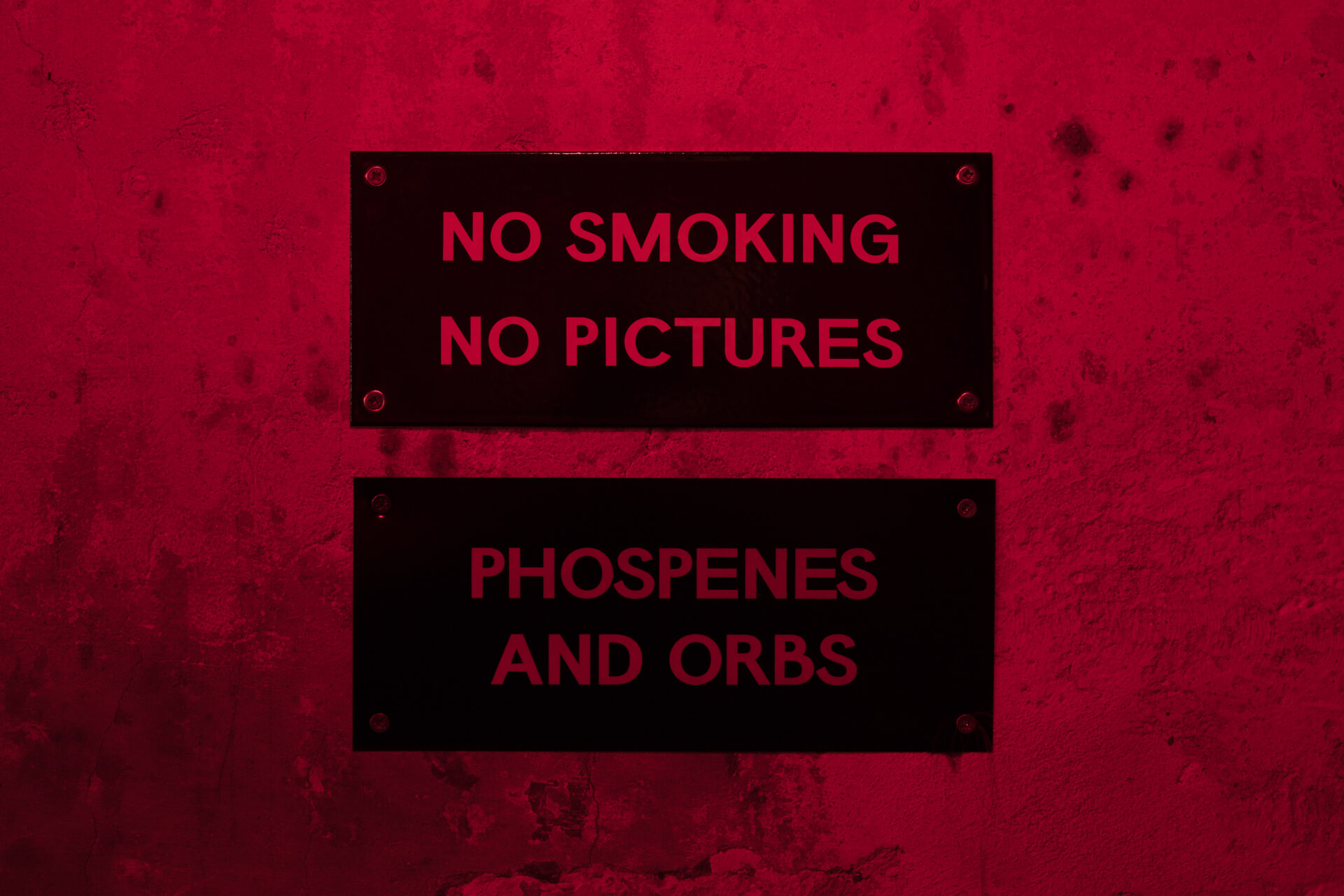

Durable Images (2019)

Another important value of the no photo policy is privacy protection. Nightlife serves as an opposite to the daily life and nightclubs provide a shelter for those seeking an escape from the daily routine. Nightspaces were always closely connected to the communities of marginalized people, to those who weren’t accepted by the majority. However free we might feel here in Prague for instance, there are still too many places in the world where being openly gay or trans is possible only in few ‘undergrounds’. Thus, a proper club has to make sure that its visitors are protected from being photographed, or published online eventually. A no photo rule is beneficial not only to those whose identity is outlawed by draconian regimes, it protects people who simply want to behave differently, experiment, flirt or try on different masks at night. The absence of cameras gives us the freedom to express ourselves and be who we want to be at the moment. It also eliminates the risk of someone using an image of you as a marketing tool.

The absence of photography

Nightclubs aren’t the only places with no photo policies of course. There are other institutions which try to create a meditative space for the presence of the human soul with the help of a photo ban. Art critic and journalist Rupert Christiansen wrote in 2014, that ‘Galleries and museums aren’t simply common public spaces in which anything goes: they are designed for calm contemplation, thought, study and reverence, places where bustle stops and hush prevails.’ Alhought clubs aren’t similar to galleries in the amount of serenity they provide, they do offer something which deserves focused attention nonetheless. However, that attention is being distracted by photographing and it has been scientifically proven: when you take a picture of something, you’re less likely to remember it in detail than something you just observe with your own yes. This is called ‘photo-taking impairment’.

Using pictures taken ‘in the club’ is another thing. It is worthy to focus on Berghain at this point because the Berlin Mecca partly owes its fame to their strict no photo policy. The absence of photography has enhanced the hype over the years, to the extent that any possible photographic account of the visit became an artefact for sharing online. Take the ink stamp for example. The mark given to the visitor was the first visual information I saw when I learned about the ‘best club in the world’ years ago. There is an even more inventive trend of taking a picture with the club’s sticker on your mobile lens. The #berghainsticker thread in instagram search is full of colorful monochromes, digital evidence of the accomplishment.

These trends represent the power of the mythology built around the club and these photographs are a social commodity, a proof of authors’ relevance within the scene. It is hard not to see the parallel with the aforementioned commodification process happening with the arrival of the interned described by Richman. She further explains that time spent in a club is a time of identity and community building for young people, and also a time for performing yourself, leisure or networking. With a shout-out to Marx’s critical analysis of commodification, Richman writes that a time spent like this is also a working time. ‘The labor that creates a product is hidden when that product enters the economic market as a commodity. The Club Kids are eventually both the workers and the product. They become the commodity.’ It is only a matter of time when some big brand finds a way to commodify sticker images or anything else with similar potential.

Club culture has always gone hand in hand with anti-systematic thinking, collective life and with the opposition of establishment. Mark Fisher explains in his essay Baroque Sunbursts, that Margaret Thatcher attacked the culture by banning raves in 1994 in the UK, concerned with the power of this new collective energy. Free time, leisure, festival, nomadic life or the new rave challenged the ways of capitalism and neoliberalism. “MDMA and electronic psychedelia generated a new consciousness, which didn’t accept the fact that boring labour is inevitable” Fisher writes. Rave didn’t go hand in hand with the individualisation and regulation of all aspects of a person’s daily life, enforced through hierarchy of power. Even nowadays, club culture still possesses this subversive quality. It can oppose conservative and backward-thinking governments, re-evaluate its identity and demographics when needed, or simply break the status quo. With all that in mind, I think that restriction of photography, one of the most valuable commodities of the modern world, is a step against capitalism, whether conscious or not. No photo policy can minimize the commodification through photography, or slow down turning the subculture into a mass one.

…club culture still possesses this subversive quality. It can oppose conservative and backward-thinking governments, re-evaluate its identity and demographics when needed, or simply break the status quo.

Clubbing’s authenticity is facing many challenges. Since it became a worldwide phenomenon and a business worth $7.1 Billion, it’s easy to forget what this world is really about. Restricting use of photography is a powerful tool for securing and reminding true values, even if not that obvious at first sight. The three images used above are a part of a documentation of my semester work from 2019 titled Durable Images, installed at Ankali. It’s a system of metal signs which intervene into the existing system of no photo signs placed around the club. Signs mimic its appearance and language, but instead of restricting and denoting rules, they challenge the viewer to think about the use of photography or rules in general. They challenge the viewer’s imagination of what might be ruined when photography is present, or what one might witness when the photography is absent.